[Source: Source: Los Angeles Times] The war on smog has been called one of America’s greatest environmental successes. Decades of emissions-cutting regulations under a bipartisan law — the 1970 Clean Air Act — have eased the choking pollution that once shrouded U.S. cities. Cleaner air has saved lives and strengthened the lungs of Los Angeles children.

But now, air quality is slipping once again.

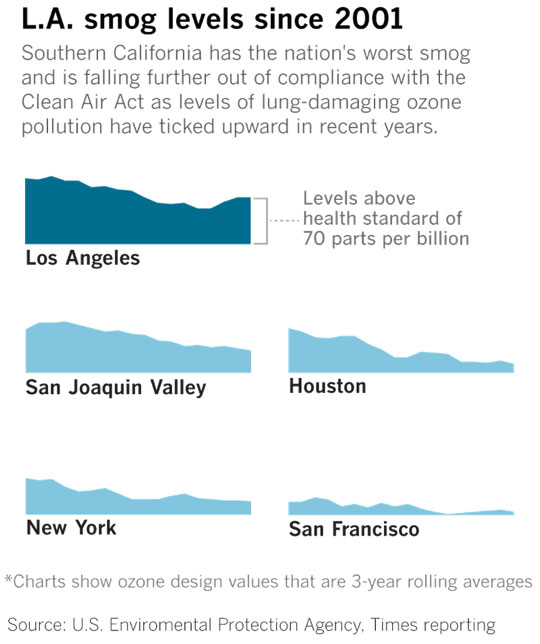

Bad air days are ticking up across the nation, and emissions reductions are slowing. The most notable setback has been with ozone, the lung-damaging gas in smog that builds up in warm, sunny weather and triggers asthma attacks and other health problems that can be deadly.

Health effects from ozone pollution have remained essentially unchanged over the last decade — “stubbornly high,” according to a study published this year by scientists at New York University and the American Thoracic Society.

Nowhere is the situation worse than in Southern California, where researchers found a 10% increase in Southern California deaths attributable to ozone pollution from 2010 to 2017. The region has long reigned as the nation’s smog capital and has seen a resurgence of dirty air in the last few years, one that has sharpened the divide between wealthier coastal enclaves with cleaner air and lower-income communities further inland with smoggy air.

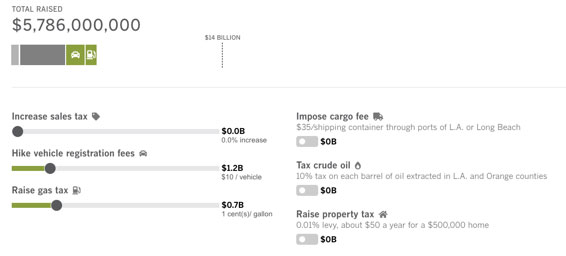

By the end of this year, California regulators must present the federal government with a plan demonstrating they are on track to slash ozone pollution. Officials say it will take billions in spending to meet smog-reduction deadlines under the Clean Air Act. But no one knows where the money will come from.

There are other obstacles, such as the Trump administration’s efforts to roll back emissions standards that California relies on to reduce pollution from cars and trucks. With each passing year, Southern California smog regulators are falling further behind in raising the $14 billion they say is needed to pay for less-polluting vehicles and clean the air to federal health standards.

Coastal-inland divide

Within Southern California, the amount of pollution you breathe is highly dependent on where you live.

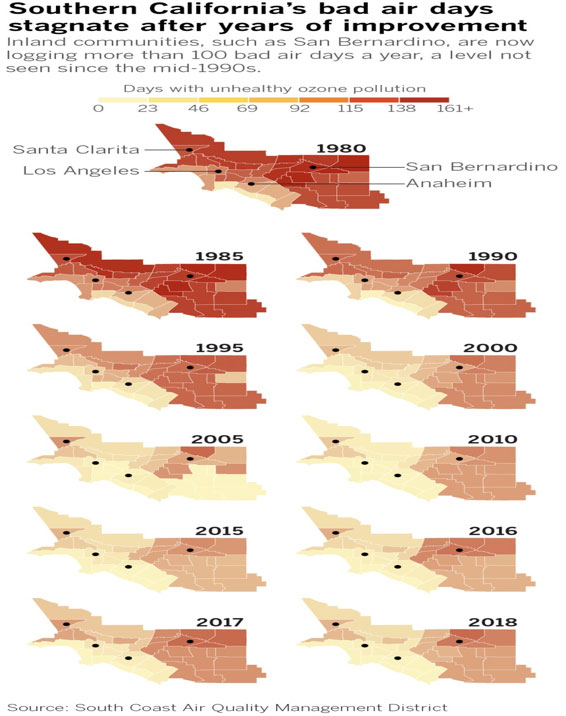

Smog has eased considerably across the region compared with decades ago. The gains are particularly dramatic in areas closer to the coast such as L.A.’s Westside and downtown, which are now largely spared persistent unhealthy levels of ozone pollution. It’s another story farther inland, where communities such as San Bernardino continue to suffer more bad air days, elevated smog levels and some of the highest asthma rates in the state.

In 2018, there were only two bad air days for ozone pollution on the Westside and just four in downtown L.A. Not far away in the San Fernando Valley there were 49. San Bernardino had 102 — more unhealthy days than the city has logged since the mid-1990s, air monitoring records show.

“We’re not seeing the same improvements as people living near the coast,” said Anthony Victoria of the Riverside County-based Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice. “When you’re in San Bernardino you look toward the mountains and it’s not clear. You have layers of smog you can see in the sky. You have people with asthma struggling to breathe, and it’s a devastating thing.”

The disparities are largely a function of weather and topography. Southern California’s persistent sea breeze blows emissions from cars, trucks and factories inland, where it bakes in the abundant heat and sunlight to form ozone pollution. The smog gets trapped against the mountains, while strong inversion layers keep it close to the ground where millions of people breathe.

“Our geography is perfect for forming ozone, and that’s what makes it such an intractable problem,” said Suzanne Paulson, a professor of atmospheric chemistry who directs the Center for Clean Air at UCLA.

Obstacles loom

Climate change is another reason ozone pollution has stopped improving, air quality experts say. Higher temperatures make smog harder to control by speeding up the chemical reactions that form ozone.

An American Lung Assn. report this year found air pollution rising across much of the nation in 2015, 2016 and 2017 — the three warmest years on record globally. The National Climate Assessment by U.S. federal agencies last fall said “there is robust evidence from models and observations that climate change is worsening ozone pollution.”

President Trump, meanwhile, has sought to roll back an array of air quality and climate change regulations and taken other steps to undermine the science underpinning them. His administration’s move to weaken the nation’s auto emissions standards, while taking away California’s ability to set its own tougher limits, could further hamstring the ability to curb vehicle pollution in the state and 13 others that follow its rules.

Potential consequences

The stakes are high not just for health but also for the economy.

If California regulators fail to submit an adequate smog-reduction plan by the end of this year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency could begin imposing a series of escalating sanctions, including increased restrictions on polluting industries and the loss of federal highway funds. Even more draconian measures could take the form of no-drive days and gas rationing. Airports and shipping harbors could also face limits on emissions.

Some clean-air experts say that’s a remote possibility, but the region’s top air quality regulator, Wayne Nastri of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, disagrees. At a May public meeting, he said the Trump administration “would jump at the opportunity to withhold funds immediately — even beforehand if they could.”

An EPA spokeswoman responded with a statement saying “EPA will continue to work closely with South Coast AQMD on air quality improvement plans.”

To meet looming federal deadlines, regulators say the region must slash emissions by more than half in the next several years — a feat that will require a rapid shift to electric vehicles and other cleaner technologies.

Funding elusive

The South Coast air district is falling short of that goal. The smog cleanup plan it adopted two years ago relies on finding $1 billion a year to help pay for cleaner vehicles and equipment, with a total of $14 billion needed by 2031. So far, officials are on track to raise only about a quarter of that amount.

Air district officials, after first floating a hike in vehicle registration fees, had been pinning their hopes on Senate Bill 732, legislation that would allow them to seek voter approval to raise the sales tax in L.A., Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties and generate billions for clean-air projects. In May, the air district-sponsored bill was pulled by its author after running into opposition from cities, transportation agencies and taxpayer groups, and it isn’t expected to be taken up again until next year.

State lawmakers added constraints in their latest budget by diverting greenhouse gas-reduction money to pay for clean drinking water projects, putting out of reach more dollars that could have been used to clean the air.

So what is Plan B?

“We’ll go to the feds and to the state,” South Coast air quality board Chairman William A. Burke said. “Our Plan B and C was our Plan A.”

Source: Los Angeles Times

July 1, 2019