[Source: Los Angeles Times] Over and over in their decades-long war on smog, Southern California regulators have failed to use a powerful tool against ports, warehouses and other freight and logistics hubs that are magnets for air pollution.

Now, the South Coast Air Quality Management District is considering a proposal to regulate warehouses, rail yards and large development projects as indirect sources of pollution due to the droves of diesel trucks, locomotives and construction equipment they attract.

But the district’s governing board again appears poised to reject much of its staff’s proposal at a public meeting Friday.

Key appointees have voiced reluctance to crack down on an industry that is both the lifeblood of the Southern California economy and responsible for much of the region’s harmful emissions. Business groups and the city-owned ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach oppose such rules, saying they will hinder growth in a sector that employs hundreds of thousands of people across the region.

One opponent is Los Angeles Councilman Joe Buscaino, a Democrat whose position against regulations on warehouses and development projects makes it unlikely those proposals will win majority support of the 13-member board. The panel consists of elected officials and other appointees from Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties: six Republicans, six Democrats and one unaffiliated member who is an environmentalist.

The decision follows more than a decade of air district proposals to use its authority under state law to regulate indirect sources of pollution, including at the ports and new development projects. None have made it past the drawing board.

At the same time, an increase in goods moving through the ports is helping drive a dramatic sprawl of new warehouses and distribution centers in the Inland Empire — and with them more pollution-spewing diesel trucks.

“There doesn’t seem to be any end to these warehouses continuing to push closer to our neighborhoods,” Kathleen Dale of Moreno Valley told regulators last month. “We need your help to fix this problem.”

A failure to pursue rules would mark another setback in the air district’s obligations to clean the nation’s worst smog and ease rates of asthma, lung cancer and other illnesses suffered by those hardest hit by freight emissions.

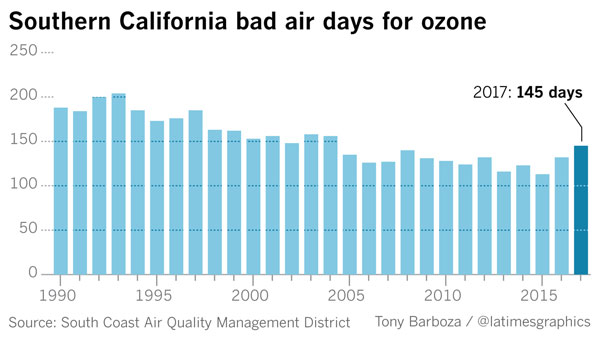

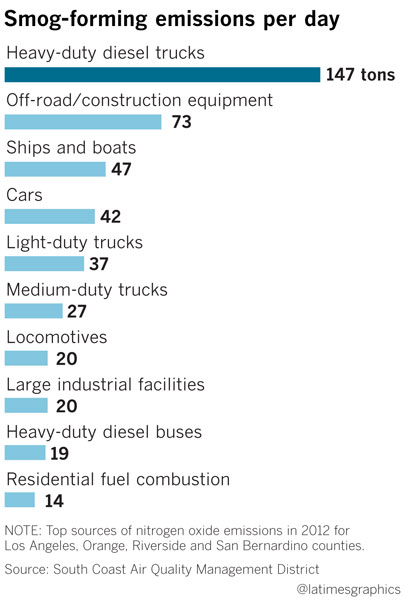

Following decades of improvement, efforts to reduce ozone, the lung-damaging gas in smog, have faltered in recent years, with the number of bad air days ticking up. Cargo ships, trucks, trains and other diesel engines are the biggest polluters in Southern California and the greatest obstacle to residents breathing clean air.

Buscaino acknowledged at a public hearing last month the importance of addressing truck pollution, but asked why the air district would “potentially negatively impact the development of warehouses” and suggested state regulators “do their part to step up” emissions requirements. “It’s important that we stay in our lane.”

Buscaino, whose district includes the L.A. port, also expressed reservations about imposing fees on development projects “while we’re in the middle of a statewide housing crisis.”

Though an air district legal memo concludes that the board has the authority to regulate rail yards, Dwight Robinson, a Republican Lake Forest city councilman on the air district board, said he remains “concerned about federal preemption issues as they relate to indirect source rules we may create for warehouses and rail yards that would likely impact interstate commerce.”

The proposal comes a year after the panel adopted a 15-year smog-reduction plan that did not include rules for ports, warehouses and rail yards. Instead, the board opted for a voluntary approach that asked those facilities to devise their own pollution-cutting measures, but pledged to return in a year and pivot to regulation if progress wasn’t made.

Now, the air district has proposed entering into voluntary agreements, rather than rules, for the region’s ports and airports. But staff recommended drafting regulations for three types of facilities they say have not made sufficient progress: warehouses and distribution centers, rail yards, and new and redevelopment projects.

The California Air Resources Board, meanwhile, has declined to pursue statewide rules on indirect pollution from freight facilities that its governing board recommended last year.

State air board chair Mary Nichols said at a meeting last month in Riverside that she is “pretty well convinced that the authority to adopt an indirect source review rule lies with the districts and must be exercised by them.”

Instead, the state over the next several years will seek to tighten rules on port trucks, cargo-handling equipment, rail yard locomotives and other freight operations as part of a push toward lower-polluting and zero-emission technologies.

Industry has fought the South Coast district’s attempts to regulate freight-handling facilities, saying they should not be held responsible for pollution from trucks and other vehicles they cannot control.

“Any facility-based measures on warehouses, rail yards or ports will harm the entire supply chain,” said Thomas Jelenić, vice president for the Pacific Merchant Shipping Assn., which represents marine terminals and ocean carriers at the ports.

Other business representatives point to past improvements in air quality as reason to shelve the proposals.

“Respect the steady progress that has been made to date by our sea and airports, and thousands of truck owner-operators using voluntary measures,” Bill La Marr, executive director of the California Small Business Alliance, told regulators. “They’ve shown the pathway to clean air doesn’t have to be through a minefield of rules.”

Local smog regulators, whose jurisdiction is generally limited to stationary facilities such as oil refineries and factories, complain they lack authority over vehicles and other mobile sources that generate more than 80% of smog-forming emissions. But air districts is several other regions of the state have already used their authority to regulate indirect pollution at new development projects, according to a South Coast district staff report.

Environmentalists say that creates an obligation to act under state law, which says air districts must work quickly to meet air quality standards using “every feasible measure.”

“If the agency doesn’t adopt mandatory regulations to clean up warehouses and other large freight facilities, they can’t claim they’ve done everything possible to solve our air pollution crisis,” said Adrian Martinez, an attorney for the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice.

San Joaquin Valley air quality officials have regulated indirect pollution sources since 2006 through a rule requiring many new developments, including warehouses, retail centers and housing projects, either use cleaner equipment during construction or pay a mitigation fee to fund emissions reductions elsewhere.

The program has reduced more than 12,000 tons of smog-forming nitrogen oxides, according to the Valley Air District, much of that achieved through $31 million in mitigation fees that have paid for emissions-reduction projects such as cleaner farm tractors and electric vehicle rebates.

But in Southern California, efforts to control indirect sources of pollution proved unpopular even a generation ago when smog was dramatically worse.

In the late 1980s the South Coast district adopted an indirect source rule that required many employers to implement ride-share programs and mass transit incentives to reduce pollution from solo commutes. The measure generated a stream of complaints from businesses, and its carpooling mandates were killed by state lawmakers in 1995.

To meet looming federal deadlines to clean ozone pollution, the South Coast basin must slash nitrogen oxide emissions an additional 55% by 2031. To do so, the district says it must increase funding for cleaner vehicles to $1 billion a year, but so far is falling short.

Trade and logistics growth has complicated the equation. In the last five years more than 100 million square feet of new industrial construction has gone up in Southern California, most of it warehouses and distribution centers in the Inland Empire, according to research by Los Angeles-based real estate services firm CBRE Group Inc.

Responding to residents urging rules at a meeting last month, Nichols said the proliferation of warehouses has “not gone unnoticed. It’s a really serious problem,” and the Air Resources Board was watching the South Coast district very closely and “hoping that they will do the right thing.”

“And if some reason they don’t,” Nichols said, “then we will have to take action.”

Source: Los Angeles Times

April 5, 2018