[Source: Los Angeles Times] The warning signs appeared soon after Denise Kawamoto accepted a job at Today’s Fresh Start Charter School in South Los Angeles.

Though she was fresh out of college, she was pretty sure it wasn’t normal for the school to churn so quickly through teachers or to mount surveillance cameras in each classroom. Old computers were lying around, but the campus had no internet access. Pay was low and supplies scarce — she wasn’t given books for her students.

She struggled to reconcile the school’s conditions with what little she knew about its wealthy founders, Clark and Jeanette Parker of Beverly Hills. When Kawamoto saw their late-model Mercedes-Benz outside the school, she would think: “Look at your school, then look at what you drive.”

“That didn’t sit well with us teachers,” she said.

The Parkers have cast themselves as selfless philanthropists, telling the California Board of Education that they have “devoted all of our lives to the education of other people’s children, committed many millions of our own dollars directly to that particular purpose, with no gain directly to us.”

But the couple have, in fact, made millions from their charter schools. Financial records show the Parkers’ schools have paid more than $800,000 annually to rent buildings the couple own. The charters have contracted out services to the Parkers’ nonprofits and companies and paid Clark Parker generous consulting fees, all with taxpayer money, a Times investigation found.

Presented with The Times’ findings, the Parkers did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

How the Parkers have stayed in business, surviving years of allegations of financial and academic wrongdoing, illustrates glaring flaws in the way California oversees its growing number of charter schools.

Many of the people responsible for regulating the couple’s schools, including school board members and state elected officials, had accepted thousands of dollars from the Parkers in campaign contributions.

Like other charter operators who have run into trouble, the Parkers were able to appeal to the state Board of Education when they faced the threat of being shut down; the panel is known for overturning local regulators’ decisions. A Times analysis of the state board’s decisions has found that, over the last five years, it has sided with charters over local school districts or county offices of education in about 70% of appeals.

California law also enables troubled charter operators to escape sanction or scrutiny by moving to school districts more willing to accept them. The Parkers have used this to their advantage, keeping one step ahead of the regulators.

“They’re like cats,” said Kawamoto, who began working at one of the couple’s charter schools in 2006. “They have so many lives.”

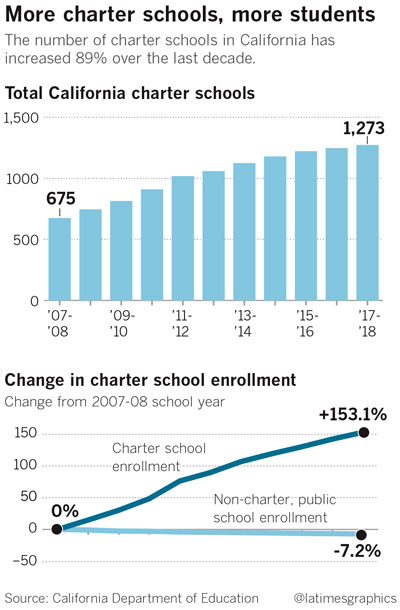

California now has more than 1,300 charter schools — more than any other state.

Twenty-seven years ago, when California became just the second state to enact a law establishing charter schools, state leaders framed the experiment as a modest one that would allow only 100 schools at first. Free-market advocates saw charters as a way to empower all students to choose from a variety of schools. Other supporters envisioned them as laboratories for testing new teaching methods and then bringing successes back to traditional public schools.

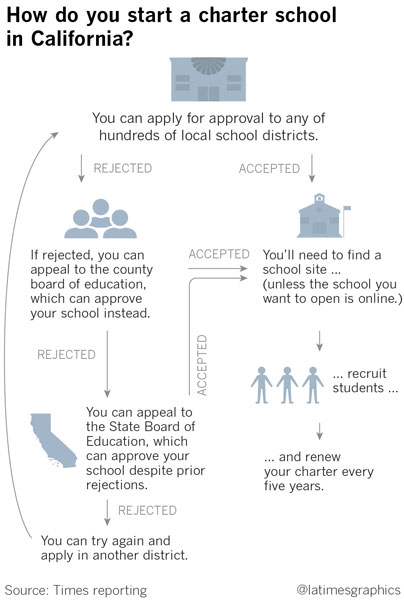

The new, privately operated schools would be government-funded and tuition-free. They would unleash creativity by liberating schools from many of the state education code’s rules. But to ensure that they lived up to their promises and spent public money properly, they would have to be vetted and overseen by governmental bodies, beginning with the school districts in which they were located.

That was sufficient check and balance for the civic-minded individuals who ran many charter schools. But as the number of charters in the state grew, the same law that allowed many founders to try new ideas with great success created opportunities for others.

The law allowed for a multitude of different bodies to serve as “authorizers,” watching over the new schools. It gave oversight power not just to the state board, but also to each of the state’s many school districts and county boards of education — regardless of whether they had the ability or inclination to properly police the independently run schools.

About 330 government entities have the authority to authorize and supervise charters in California. By contrast, Texas, the state with the second-largest number of charter schools, has 18, according to its state education agency. New York has two active authorizers.

Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, has an entire division devoted to overseeing the charters it authorizes and is considered one of the state’s most robust monitors. But the roster of charter authorizers also includes school districts with colorful histories of corruption and financial mismanagement. Some are so small that they have fewer than a dozen employees in all, with insufficient resources to be effective watchdogs.

The system has given rise to many well-respected charter organizations across the state, including KIPP and Green Dot Public Schools, which reach students in neighborhoods desperate for better options. But it also has allowed unscrupulous entrepreneurs to profit from a fragile and fractured regulatory patchwork.

In L.A., the founder of the charter school network Celerity Educational Group recently pleaded guilty to a felony count of conspiracy to misappropriate and embezzle public funds. Federal prosecutors found that Vielka McFarlane had used her charter schools’ credit card to pay for expensive clothing, luxury hotel stays and first-class flights for her and her family. She faces a maximum sentence of five years in prison.

Oxford Preparatory Academy, a Chino charter, was forced to close in 2017 after an audit determined that the school’s founder had been laundering state funds through her private company. Another audit found that a charter network CEO in Livermore had misspent $67 million in tax-exempt bonds and tried to mislead auditors. When the network filed for bankruptcy and closed its four charter schools, 1,500 students were displaced.

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation earlier this month requiring more transparency and stricter conflict-of-interest rules for charter schools. Those reforms could lead to changes when they take effect next year. But they are unlikely to fix the structural issues that have allowed problem charter school operators to circumvent oversight.

“There are wildly different levels of attention being paid to these schools, and charter schools are finding ways to shop around for the weakest oversight,” said Greg Richmond, president of the National Assn. of Charter School Authorizers. “As long as California’s authorizing structure stays fragmented across more than 300 different entities, you’re going to keep having these problems.”

The Parkers live in a 7,700-square-foot home in Beverly Hills with an estimated value of about $15.3 million.

Jeanette Parker is a past president of the Beverly Hills Republican Club, author of the self-published book “Will You Marry Me? Jesus Christ Proposes to You!” and a regular contributor to L.A.’s largest black newspaper, the Los Angeles Sentinel, which publishes her columns on topics such as single motherhood and why eggs come in many colors. As superintendent of Today’s Fresh Start, she is paid an annual salary of about $285,000.

Her husband, Clark, is a businessman, a vendor of security devices and a real estate developer who, in an online biography, says he has “developed hundreds of commercial and residential properties” in Southern California. He sits on the board of the South Coast Air Quality Management District and lists among his accolades the title of honorary consul general of the Central African Republic.

The Parkers are in their 70s. Between them, they have two PhDs and a doctorate of theology from the University of Central Arizona (a two-man operation forced to stop conferring degrees in 1980, according to contemporaneous reports in the Arizona Republic), St. Charles University, and Pacific International University. Both St. Charles and Pacific International are listed in “Degree Mills: The Billion-Dollar Industry That Has Sold Over a Million Fake Diplomas,” a book about unaccredited for-profit colleges accused of selling degrees co-written by Allen Ezell, a former FBI agent who ran a task force on diploma mills.

In examining Today’s Fresh Start, The Times interviewed 11 current and former teachers and administrators; reviewed hundreds of pages of financial and legal records; and spoke to those responsible for overseeing the organization’s schools. It found that there were plenty of reasons to be wary of the Parkers well before the couple opened their first charter school.

The couple’s first foray into education was in 1968, when they opened a collection of day-care centers in South L.A. under the name Golden Day Schools. As director, Clark Parker won lucrative state contracts to enroll children from low-income families — until 2011, when state officials cut him off, citing “serious, chronic, and systemic program violations.”

Two state audits of the day-care program accused the nonprofit of falsifying records, padding attendance figures and spending public money to pay above-market rent for properties owned by the Parkers. The organization, which the state said Clark Parker oversaw, had also used public funds to reimburse itself for parking tickets, Clark Parker’s personal property taxes and vehicle registration fees for his Rolls-Royce and Mercedes-Benz — costs that state investigators determined had nothing to do with child care.

In 2003, the Los Angeles County Office of Education approved Jeanette Parker’s petition to open a charter school.

Over the next 16 years, Today’s Fresh Start expanded from a single campus to the three sites it currently operates in Los Angeles, Compton and Inglewood. Enrollment swelled from 282 students to 1,150 in grades K-8 last school year. The vast majority of its students are African American or Latino children from financially struggling families.

“As soon as we approved them, we started getting signs they weren’t really operating in the best interests of students and teachers,” said Darline Robles, a USC professor of education who was superintendent of the Los Angeles County Office of Education when it authorized Today’s Fresh Start.

In 2007, a Today’s Fresh Start teacher tipped off Robles’ staff to the possibility that the charter was tampering with the state’s standardized tests. An investigation ultimately found that something had gone wrong — students had been asked to revisit portions of the exams they had already completed. No one could say how many children had participated, or at whose direction, but it was serious enough that county officials proposed sending monitors to oversee testing.

Jeanette Parker refused, writing, “There is no state law requiring proctors.”

In response, the county widened its inquiry.

Officials learned that Today’s Fresh Start was renting buildings owned by the Parkers and paying Golden Day Schools, their state-funded child-care business, to provide food for the charters’ students. The charter network had also spent most of a $50,000 state grant to hire an unaccredited university to recommend ways to improve its charter schools. That university was founded by Jeanette Parker.

Accused by the county of self-dealing, financial conflicts of interest and wrongly administering the state tests, Jeanette Parker rejected the county’s findings. She said she already had addressed her financial interest in contracts and leases by recusing herself from voting on them, leaving those decisions to the charter network’s governing board.

That was an argument that could stand up only if the network’s board was independent. But county officials found that more than half of its members — who included the Parkers — had a financial stake in the schools.

“Thus, it appears that Jeanette Parker approves her own actions, evaluates her own performance, sets her own salary and single-handedly decides what will occur at TFSCS,” county officials wrote in a report laying out the case for revoking the charter.

In late 2007, the L.A. County Board of Education voted to close Today’s Fresh Start, citing more than 50 legal and regulatory violations.

In late 2007, the L.A. County Board of Education voted to close Today’s Fresh Start, citing more than 50 legal and regulatory violations.

In states such as New York or Massachusetts, where the power to authorize and oversee charter schools is concentrated in the hands of a select few regulatory bodies, that might have marked the end of the Parkers’ journey. In California, it was only the beginning.

In states such as New York or Massachusetts, where the power to authorize and oversee charter schools is concentrated in the hands of a select few regulatory bodies, that might have marked the end of the Parkers’ journey. In California, it was only the beginning.

The Parkers sued the county to try to get its decision overturned and keep their schools open. While that case was pending, they appealed to the State Board of Education, an 11-member body appointed by the governor that has the power to overrule decisions by school districts and county boards.

The board often grants appeals to charters that have been rejected elsewhere, sometimes for serious financial and academic failings. Though it is supposed to be a standard-bearer of sorts for other authorizers, the state board has a reputation for leniency.

Charter schools approved by the state board “win by losing,” said Thomas Saenz, a civil rights attorney who sits on the L.A. County Board of Education and voted to revoke Today’s Fresh Start’s charter. “They lose in front of the school district or the county, but they win because they get the state as an overseer, and that means they get less oversight.”

In 2010, the year they made their case to the state board, the Parkers spent $15,000 on lobbyists. An NAACP representative came out to support them, as did former Lt. Gov. Mervyn Dymally, who in the course of his political career had received tens of thousands of dollars from the Parkers.

“I might have been lobbied for Today’s Fresh Start more than any other vote I cast on the state board,” said former state board member Ben Austin, who had misgivings about allowing the charter to stay open.

Austin said he was especially troubled by the charter’s academic performance. Its test scores swung wildly, from lows that landed it on a state list of “persistently lowest-achieving” schools to large increases in the span of a year. The pressure to approve the charter was intense, he said.

“I’m white. And I was getting lobbied by African American leaders to vote in a way they perceived would serve the African American community,” Austin said. “That’s a fairly uncomfortable position to be in.”

Recordings of state board meetings show there was little discussion of the L.A. County Board of Education’s findings of self-dealing, regulatory violations and testing irregularities. Problems at the Golden Day centers didn’t come up.

State Supt. of Instruction Jack O’Connell led department staff in recommending that the board keep Today’s Fresh Start open, which the board — including Austin — unanimously approved. The new school year was only weeks away and if the vote had been no, hundreds of students would have had to scramble to find a new school.

During O’Connell’s two terms in office, campaign finance records show, the Parkers had donated more than $73,000 to his various political committees. O’Connell said the money played no role in his decision.

“In the case of Fresh Start, it was one of those occasions where I agreed with the state board,” he wrote to The Times. “The charter served an overwhelming number of low-income, minority kids that I believed would contribute to my overarching focus on closing the achievement gap.”

Austin wasn’t as confident. In retrospect, he said, “I’m not sure it was the best outcome for kids.”

Several months after the state board voted to renew Today’s Fresh Start’s charter, a teacher contacted county and state education officials.

“I would like to report on a school in Los Angeles that is run poorly and is a danger to their students,” wrote Andrew Goudy on the first of nine pages that detailed problems including cracks in classroom walls, broken air-conditioning and heating systems, and cafeteria food served spoiled or undercooked. He had, he wrote, maybe one textbook for every three students.

Goudy wrote that he’d overheard an administrator call several students a “total waste” and speak of the opportunity “to get rid of” those with disabilities.

Years later, in an interview with The Times, he said he had never worked at a school that showed so little regard for students’ well-being.

“Every day, it was like, what should I do?” Goudy said. “Should I run in there and call 911? Should I just get out and work at Starbucks?”

The choice, he said, was made for him. Shortly after he sent the emails, he said, he was fired.

A state employee emailed back, promising to address his concerns. It’s unclear if anyone did. As years went by, Goudy lost hope that there would ever be consequences. He died in October 2018 at the age of 48.

In interviews, former and current Today’s Fresh Start teachers echoed his concerns. The more experienced among them said they knew the charter was receiving millions of dollars in government funding each year — an amount tied to its enrollment — but they could not see evidence of where the money went.

When Yanin Ardila was hired in 2009, she arrived to find no workbooks, notebooks or crayons for her students, she said. Half a dozen kindergartners had been plopped into her first-grade class because they didn’t have a classroom or a teacher of their own. On a few occasions, she said, she had to intervene to stop the staff from serving children bread that was past its expiration date.

In a 2014 interview with Beverly Hills Weekly, Jeanette Parker said her motives for opening Today’s Fresh Start were charitable.

“I wanted to start the charter school personally because I saw the need to educate the inner-city youth,” she told the weekly newspaper. She had grown up in Birmingham, Ala., with little money, she said. She wanted to reach students like herself.

Ardila saw it differently. “They didn’t care about students, it was just about money,” she said of the school’s leaders.

After spending a year in a cockroach-infested classroom, she said, she was moved into a nicer space. But the school remained a chaotic place. She left after three years for a job at another charter school.

Kawamoto, the former Today’s Fresh Start teacher who wasn’t given books for her students, said she was suspicious of the odd way in which she was paid. She said she was told to fill out two sets of time cards, making it seem as though she divided her time between the charter school where she worked and one of the Parkers’ day-care centers, which operated out of the same location. At the end of each month, her salary was split into two paychecks, she said. Goudy and Ardila — who had never worked for Golden Day — said they also were paid in this way.

While Today’s Fresh Start was under the county education board’s oversight, officials there tried to interest the L.A. County district attorney’s office in investigating the Parkers’ financial practices. Prosecutors began an inquiry but closed it after interviewing two teachers, according to a memo the office provided to The Times. “There does not appear to be any fraud involved,” they wrote.

In its 2011 audit of the Parkers’ day-care operations, the state reached a different conclusion. It found that as Golden Day’s director, Clark Parker had been systematically overbilling the state Department of Education and using money meant for his day-care centers to pay the salaries of Today’s Fresh Start employees.

In court filings, Parker disputed the state’s account. He said that some of his employees had worked for both the day-care centers and the charter schools. The audit “is flawed and it should be dismissed because it is written by Biased Auditors and it is based on speculation,” he wrote in a request for an appeal.

State officials were not persuaded; they stopped funding the day-care centers.

The state Department of Education is currently suing Golden Day and Clark Parker to recover more than $19 million it says the nonprofit misspent. State officials had decided they could no longer trust Clark Parker to run a day-care business, but they allowed his wife’s charter schools to stay open.

Staying in business required Today’s Fresh Start to keep moving from one authorizer to another.

In 2009, the Parkers persuaded the Inglewood Unified School District to let them operate a school under its oversight. With the help of a nearly $20-million facilities grant from the state, the couple built a large, boldly colored school building on a stretch of Imperial Highway known for prostitution.

Inglewood proved to be unequipped to oversee a charter school.

In 2012, with its finances in complete disarray, the district was taken over by the state Department of Education. Overwhelmed and subjected to a rotating cast of state-appointed leaders, it paid little attention to the district’s charters. Asked for copies of charter oversight and inspection reports dating back to when it first authorized Today’s Fresh Start, the district said it had none.

Oversight in Inglewood was so lax that in 2015, when the Parkers asked to have their charter renewed, district officials sat on the request, blowing a 60-day deadline. As a result, Today’s Fresh Start’s Inglewood charter was automatically renewed until 2020.

State Administrator Thelma Meléndez, who was chosen in 2017 to lead the district, said that Inglewood doesn’t have the staff to oversee its charters as rigorously as a large district such as L.A. Unified. Like many small districts, it can’t afford to devote even one employee to the task full time. There are signs, however, that Meléndez is paying more attention than her predecessors. Earlier this month, she sent Jeanette Parker a letter expressing concern over the charter’s test scores and asking for a detailed plan for their improvement.

Inglewood gave the Parkers a secure foothold, but it was only a partial answer to their problems.

Jeanette Parker had never stopped fighting the county’s decision to revoke her charter — even though the State Board of Education had taken over the county’s supervisory duties. In 2015, when the California Supreme Court upheld the revocation, and other regulatory changes took effect, Today’s Fresh Start could no longer operate its schools in South L.A. and Compton under the state board’s oversight.

The Parkers, looking for a lifeline, turned to the two districts in which the schools were located: L.A. Unified and Compton Unified.

Officials in L.A. took a hard look at Today’s Fresh Start and saw how the Parkers’ schools had become more entangled with their financial interests.

Officials in L.A. took a hard look at Today’s Fresh Start and saw how the Parkers’ schools had become more entangled with their financial interests.

After five years under state oversight, they were still using public money to rent buildings they owned.

Clark Parker was no longer on the board of Today’s Fresh Start — he was on the payroll. Board minutes showed that his wife’s schools had hired him to manage construction of the Inglewood school. His initial contract was for $575,000.

In a strongly worded report to the school board, L.A. Unified officials wrote that the Parkers had potentially broken California’s conflict-of-interest laws. They were also concerned about the charter’s academics. Although officials found Today’s Fresh Start’s test scores acceptable, they wrote that the charter was struggling with English learners. These students made up 30% of the charter’s population, yet over a two-year period, not a single one had been reclassified as English-proficient.

The Parkers denied any wrongdoing. In a speech to the board, Clark Parker said that Today’s Fresh Start should be judged on how much it had raised its students’ test scores, not on other issues. The schools were trouble-free, he said, “not one incident of any problem at all.”

The Parkers denied any wrongdoing. In a speech to the board, Clark Parker said that Today’s Fresh Start should be judged on how much it had raised its students’ test scores, not on other issues. The schools were trouble-free, he said, “not one incident of any problem at all.”

The couple’s lawyer argued that L.A. Unified was unfairly holding them to a stricter conflict-of-interest law that applied to district-run schools. The law that applied to charters was different.

The L.A. school board rejected Today’s Fresh Start’s petition.

If the charter schools were going to stay open, the Parkers would need to find another authorizing body.

In July 2015, Today’s Fresh Start became the first charter approved by Compton Unified, a district that had been struggling under a cloud of mismanagement and corruption for decades. Compton assumed responsibility for overseeing two of the group’s sites — one in Compton and one in South L.A.

In response to questions from The Times, district Supt. Darin Brawley said that he had visited the schools twice, most recently in 2017. But when asked for records from these visits, district officials said they had none. Nor did they have any of the financial records, such as bank statements, annual tax filings, contracts or lease agreements, that vigilant authorizers use to monitor charter schools.

The Parkers became major donors to the political campaigns of two Compton Unified board members.

Compton school board races are often small-time affairs. With unions picking up the cost of mailers and phone banking, candidates have raised less than $10,000 and still won. The Parkers wrote large checks — over the course of the last several years, they have given more than $21,000 to Compton Unified board President Micah Ali and Vice President Satra Zurita.

Neither Ali nor Zurita responded to requests for comment.

In late 2017, as Compton was considering whether to renew Today’s Fresh Start, district staff prepared a report listing some of the charter petition’s deficiencies. They noted that Jeanette Parker had not disclosed who was on her organization’s board or whom her charter was doing business with.

“Please note that the petition is generally vague and inconsistent regarding the details of the programs outlined in the petition,” the report said.

Still, district officials recommended renewal. They had been assured, Brawley said, “that the deficiencies identified in the petition would be rectified.”

When the charter’s renewal came up in December, Compton school board members did not discuss the charter’s academic performance. They did not question the Parkers, who sat before them in the audience.

What they did was a foregone conclusion.

The board took less than a minute to vote unanimously to renew Today’s Fresh Start until June 2023.

Source: Anna M. Phillips, Los Angeles Times. Zahira Torres, a former Times staff writer, contributed to this report.