[Source: Earl J. Ritchie/UH Energy] Polls consistently show a high level of environmental awareness in the U.S. However, awareness frequently does not translate into action.

Use of mass transit has shown almost no per capita growth despite substantial investment in light rail and other transit improvements. Carpooling has declined.

The use of environmentally friendly technologies such as solar and wind power has grown modestly, except where subsidized or mandated. In part, this is because they have been more expensive than their fossil fuel using counterparts. However, even as those costs approach parity, growth rates drop significantly when subsidies are removed.

Models of environmental decision making

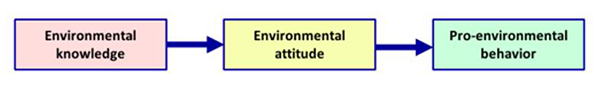

There was once, and to some extent continues to be, a belief in the simple model shown below: knowledge of the environment leads to a positive environmental attitude, which results in pro-environmental action.

This has not happened consistently, either in the U.S. or Europe. In a European study, Ortega-Egea et al. say “Over the past two decades, increased media coverage – coupled with economic incentives, subsidies, and related interventions – has substantially raised citizens’ awareness and concern about climate change, but has typically failed to induce persistent behavioral changes.”

The root cause of the problem is that protecting the environment is not the only goal that people have. Individuals choose actions based upon priority between conflicting goals. In addition, there are multiple sources of influence affecting environmental choices. The influences are often subconscious.

A large number of theories have been proposed to explain what motivates environmental behavior. An entire journal, the Journal of Environmental Psychology, is devoted to the topic. A model described by Steg and Vlek includes five categories, paraphrased below:

- Perceived costs and benefits (including nonmonetary costs and benefits)

- Moral and normative concerns (what you think you should be doing)

- Emotion

- Contextual factors (primarily available means)

- Habits

In addition to these factors, political orientation, age, gender, education and other individual characteristics influence environmental behavior.

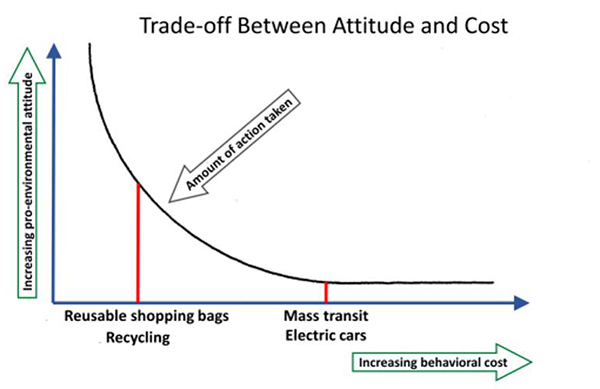

Making or saving money is a powerful motivator. It is the primary reason for the rapid growth of subsidized solar energy. However, there are differences in perception and in importance of cost, as well as nonmonetary costs, such as comfort, time and convenience. The graph shows a model of the trade-off. Things that make you feel good but require little cost, discomfort, convenience and effort, such as recycling, are likely to be done; those that have a significant number of these negatives, such as riding mass transit instead of driving, are not.

Moral and normative concerns

Individuals have multiple moral codes governing different situations and aspects of behavior. They may belong to multiple groups (friends, neighborhood, political party, nation) that do not have the same values. They vary in the extent to which they are influenced by group norms. They vary in the importance they place on environmentally friendly behavior. This creates not only conflict between norms, but the opportunity to rationalize away environmental actions.

Emotion

People derive pleasure or displeasure from actions that affect the environment. They may derive pleasure from driving a powerful car or from the status that owning such a car gives them. Environmentally oriented individuals may derive pleasure from installing a solar panel or bicycling to work.

Contextual factors

The ease or availability of means for environmentally friendly actions, or the extent to which individuals are reminded of such actions, may influence whether those actions are taken. For example, riding mass transit may not be done if the routes are inconvenient. A person may be motivated to recycle if he or she sees others recycling.

Habits

People often do not consider alternatives to their customary way of doing things. They may reject alternatives without investigation or discount evidence of their desirability.

Other behavioral models

The Steg and Vlek model is only one example of numerous published explanations of environmental choice. It is presented in outline here and does not include all factors.

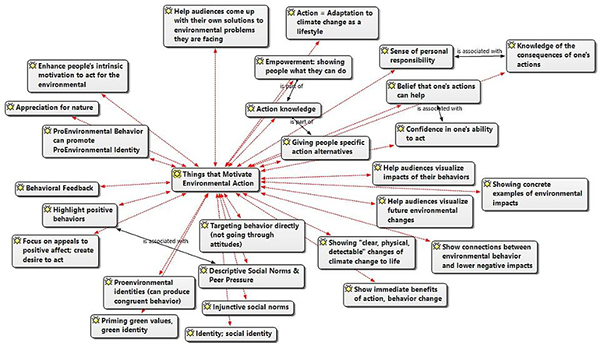

There are other theories and other ways to illustrate motivating factors, such as this one from Jarreau. It’s a complex subject.

Education may not lead to pro-environmental actions

Nearly all of the literature is normative, that is, it is assumed that individuals should adopt pro-environmental behavior. The reasons that they do not do so are usually called barriers.

It is possible to have environmental knowledge and not develop a pro-environmental attitude. For example, there is widespread belief that so-called climate change “deniers” or skeptics will be converted to belief if they are presented with scientific argument and data. However, many, including some with a strong scientific background, reject the argument. Hornsby et al. said, “A critical mass of people is skeptical that anthropogenic climate change is real.” As was shown in an earlier post, there is a strong political divide in climate change belief.

Alternatively, one might have a pro-environmental attitude but believe that other concerns have higher priority. This is a particular problem at the governmental level, where there are many demands for available funds. Environmental measures compete with social programs, national defense and other programs.

There are a number of behaviors that can be considered pro-environment, for example, reducing air pollution, protecting endangered species, preserving natural environments and reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Although there is a tendency for these beliefs to be correlated, individuals may have strong feelings about one but little interest in another. This dilutes political support.

Summary

There are numerous psychological factors influencing whether a person will take individual environmentally friendly actions or support collective and governmental actions. These can be influenced, vary over time and interact. They will have strong influence on the pace of adoption of electric vehicles, ride sharing services, and other lifestyle changes that are expected to reduce CO2 emissions and fossil fuel use.

Earl J. Ritchie is a retired energy executive and teaches a course on the oil and gas industry at the University of Houston. He has 35 years’ experience in the industry. He started as a geophysicist with Mobil Oil and subsequently worked in a variety of management and technical positions with several independent exploration and production companies. He retired as Vice President and General Manager of the offshore division of EOG Resources in 2007. Prior to his experience in the oil industry, he served at the US Air Force Special Weapons Center, providing geologic and geophysical support to nuclear research activities. Ritchie holds a Bachelor of Science in Geology–Geophysics from the University of New Orleans and a Master of Science in Petroleum Engineering and Construction Management from the University of Houston.

UH Energy is the University of Houston’s hub for energy education, research and technology incubation, working to shape the energy future and forge new business approaches in the energy industry.