[Source: The Hill] One factor contributing to the rise of populist sentiment in the U.S. has been the decline in manufacturing jobs, from 17 million in 2000 to 11 million in 2010, with a small bounce-back since then.

President-elect Trump promises to bring manufacturing jobs back. In thinking about policies that might accomplish this, it is important to keep three economic trends in mind.

First, job loss in manufacturing derives primarily from technological change, not from trade. Manufacturing’s share of U.S. production is quite stable, but its share of employment has declined at a steady rate because productivity growth in manufacturing is higher than in services.

This trend can be observed in all of the advanced economies, including ones such as Germany that have large trade surpluses. Manufacturing’s share of employment in Germany declined by 15.5 percentage points during 1973-2010, very similar to the U.S.’s 14.7 percentage point decline.

If the U.S. were to run a trade surplus, as Germany does, there is likely to be a one-time gain in manufacturing employment, but then the trend decline will continue.

In the event of a surplus, we would consume less of our GDP (and consumption is mostly services) and export more (U.S. exports are mostly manufactures).

Hence, there would be a one-time shift of capital and labor from services to manufacturing. Then, the trend decline of manufacturing employment would continue as long as productivity growth in manufactures is faster than that in services.

If we are going to have continuing productivity growth through technological advance, then we need policies to help workers retrain and adjust to changing labor market demands. Trying to lock the old jobs in place is not going to generate prosperity.

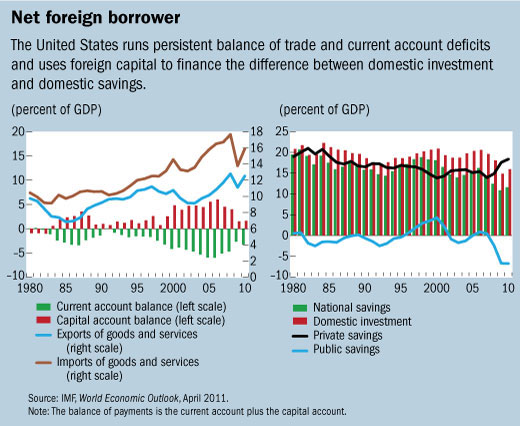

Second, the broadest measure of the trade balance, the current account, is equal to savings minus investment. Countries with a trade deficit, like the U.S., are borrowing from the rest of the world to support investment.

In thinking about policies that affect the trade balance, we certainly do not want investment in the U.S. to go down. There is general agreement that we need more public investment in infrastructure and private investment to spur growth.

It is not clear what policy package will emerge from the new Congress and administration, but plans under discussion for a tax cut and infrastructure spending are likely to increase investment in the U.S.

The effects on savings are unpredictable — private savings may rise in the face of better investment returns, but a larger fiscal deficit means a reduction in government savings. It is quite plausible that the net effect will be an increase in the trade deficit, i.e., investment rising more than savings.

I heard one investor characterize the tax-cut plans as “making the U.S. the new Ireland.” There is likely to be a big net inflow of capital that appreciates the dollar and increases the trade deficit.

This is not necessarily a bad thing if the investment is very productive. But, if we really want to increase investment and simultaneously reduce the trade deficit then we would need policies that encourage more savings.

An obvious one would be a steep carbon tax used partly to fund infrastructure and partly to reduce the fiscal deficit. Reducing the deficit, other things equal, would reduce interest rates, lower the value of the dollar, and support tradable sectors, such as manufacturing.

Third, restrictions on imports are not likely to reduce the trade deficit. It may seem, at first glance, that an easy solution to the problem of manufacturing employment is to tax or otherwise restrict imports so that the manufacturing of those goods then has to be done in the U.S.

It is one of the curious laws of economics, however, that an import tax is equivalent to an export tax. Protecting the import-competing industries will indirectly disadvantage our export industries, many of which are manufacturing industries, such as aircraft.

One way this happens in practice is that import restrictions lead to an appreciation of the currency that makes life difficult for exports. All of this is true irrespective of our partners’ reactions.

In the real world, it is likely that major partners, such as China, will retaliate with their own import restrictions. So, everyone’s imports and exports will contract and we will all be worse off.

It is hard to estimate the net effect on the trade balance in these complicated scenarios, but then, it is useful to keep the second point in mind. Assuming that we want more investment, the trade deficit can only decline if there is an even larger increase in national savings.

Do we think that the trade war, with some industries benefiting and others losing, will lead to an increase in savings? Not likely.

In summary, it is extremely unlikely that any set of U.S. policies could reverse the long-term trend for manufacturing employment to fall as a share of the labor force, hence the importance of policies to support training and adjustment.

We could get a one-time increase in manufacturing employment from a large decline in the trade deficit, but this will be very hard to do if investment is increasing at the same time. It would require measures to substantially increase savings.

Trade protectionism makes us and other countries poorer and is not likely to increase our aggregate savings. “Protectionism” is an aptly chosen word as it aims to lock in place an old industrial structure, rather than helping workers and communities adjust to inevitable changes.

David Dollar is a senior fellow in the John L. Thornton China Center at the Brookings Institution. From 2009 to 2013, Dollar was the U.S. Treasury’s economic and financial emissary to China, based in Beijing, facilitating the macroeconomic and financial policy dialogue between the United States and China.

Source: The Hill

December 28, 2016