[Source: Bloomberg] The U.S. has already broken the link between emissions and economic growth.

Any regulation proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency follows a decades-long pattern. The activists squabble with the industrialists, pitting questions of business health against questions of public health. The squabbling plays out in newspapers and private lobbying meetings while the rules are drafted, and then it continues in court until somebody wins and somebody loses.

For America’s biggest environmental law, however, economic health and public health haven’t been locked in a zero-sum battle. The air is indisputably cleaner today, even after decades of economic growth. As the Obama administration tries to apply the Clean Air Act to a new environmental problem—climate change—it’s worth wondering if past performance ever guarantees future results.

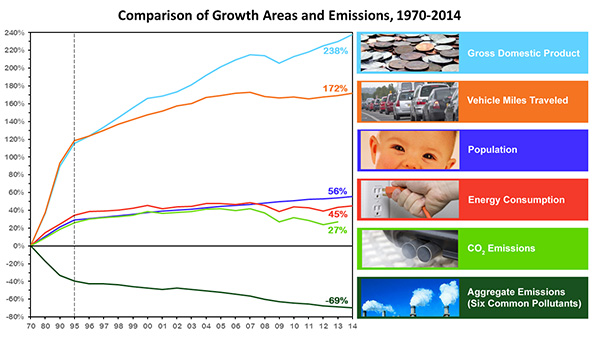

An annual report on air quality from the American Lung Association includes a revealing chart that tracks the percentage change in air pollution, gross domestic product, vehicle-miles traveled, population, energy consumption, and carbon dioxide emissions since 1970, when President Richard Nixon signed the Clean Air Act into law.

Air pollution has dropped considerably even as GDP, population, and energy consumption have increased since 1970. Source: EPA

It’s clear from the chart that even as the U.S. dramatically slashed air pollutants—including carbon monoxide, lead, ozone, and particulate matter—the economy continued to grow. While the country continued to drive cars and burn fuel, such innovations as the catalytic converter and unleaded gasoline made the pollution from those activities less noxious.

The question before the world is whether we can send climate-warming pollutants in the same direction while unlinking carbon emissions from economic growth. At the heart of the economic argument against Obama’s Clean Power Plan, which uses the EPA’s authority to phase out the most polluting coal plants, is that we just can’t afford it. An analysis commissioned by America’s Power, a group representing the coal industry, predicts that Obama’s plan would cause electricity prices to spike by double digits and could cost the economy up to $39 billion a year.

“I’ve doing this over 25 years,” said Paul Billings, senior vice president of advocacy for the American Lung Association. “I’ve heard this from industry every single time EPA has tried to tighten a standard.”

Early evidence from carbon-cutting programs suggests that economies are not left in ruins. Nine northeastern states would have produced 24 percent more emissions if they hadn’t formed the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in 2009. From 2009 to 2014, their combined GDP grew by about 8 percent. British Columbia enacted a carbon tax in 2008. Emissions per capita fell 12.9 percent below its pre-tax years—3.5 times larger than the overall decline in Canadian per capita emissions—and the province has not become an economic basket case.

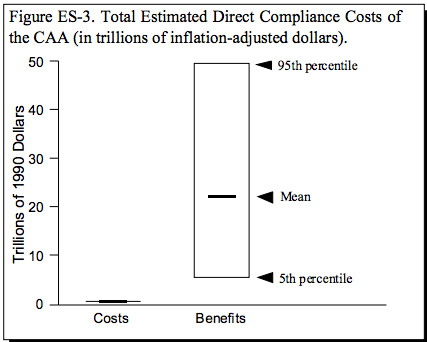

The EPA has studied the effects of the Clean Air Act repeatedly. A first major review came in the 1990s, when researchers found that from 1970 to 1990, cumulative benefits—which include reductions in deaths and illnesses from asthma, heart attacks, and stroke— outweighed costs by an average ranging from $22.2 trillion to $563 billion.

This chart shows that the benefits of the Clean Air Act of 1970 outweighed the costs by more than a factor of 40. SOURCE: “The Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act, 1970-1990—Retrospective Study”; U.S. EPA

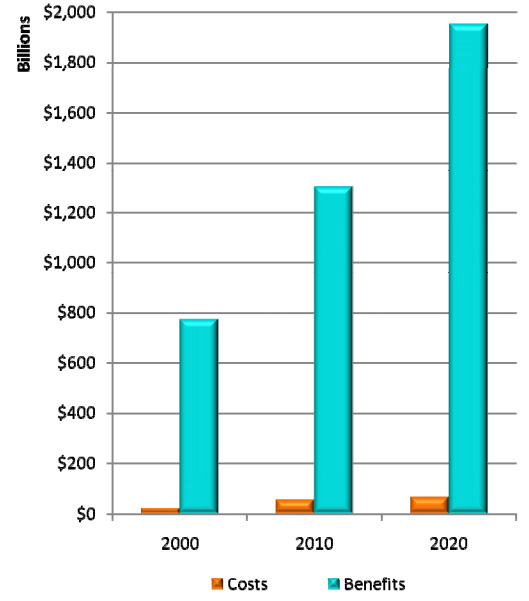

The same pattern holds for an update (or amendments) to the Clean Air Act, which President George H.W. Bush signed into law in 1990. This updated law targeted sulfur pollution from coal-burning power plants that caused acid rain. Again, the EPA found, in this 2011 report, that the benefits tower over the costs.

This graph shows how the benefits of the Clean Air Act of 1990 dwarf its costs. SOURCE: “Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act, 1990 to 2020: Second prospective study”; U.S. EPA

CO2 is even more closely tied to the U.S. energy system and economy than conventional air pollution, which complicates matters significantly. Earlier efforts prove it’s possible to reduce pollution without crimping economic growth, defying doomsayers’ predictions. If Obama’s Clean Power Plan survives, it may take decades to tell whether it can do the same.

Source: Bloomberg

April 20, 2016