[Source: Los Angeles Times] Californians are likely to pay more for gasoline, electricity, food and new homes — and to feel their lives jolted in myriad other ways — because their state broadly expanded its war on climate change this summer.

The ambitious new goals will require complex regulations on an unprecedented scale, but were approved in Sacramento without a study of possible economic repercussions.

Some of the nation’s top energy, housing and business experts say the effort may not only raise the cost of staples, but also slow the pace of job and income growth for millions of California families.

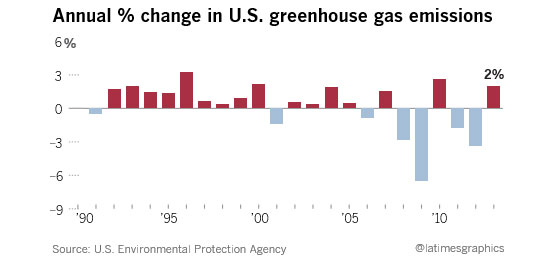

And now that Donald Trump, who has dismissed climate change, is headed for the White House, Californians may find themselves making sacrifices while the residents of other states are missing in action.

Two key laws this summer kicked California’s climate change fight into high gear.

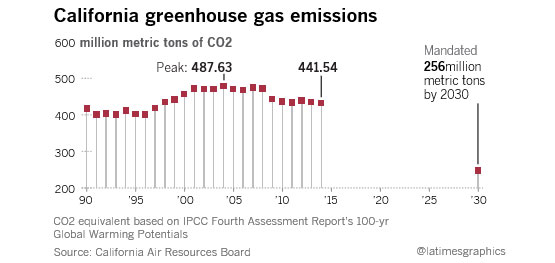

Senate Bill 32 requires the state to cut greenhouse gases 40% below their level of 1990 — based on evidence that a global reduction at that level would limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius above the temperature levels of a few decades ago.

Senate Bill 1383 requires similar reductions in methane, refrigeration gases and black carbon.

Before signing SB 32, Gov. Jerry Brown said he didn’t expect problems.

“California is doing something no other state has done,” he said. “We are bringing into law real measures backed up by the real power of the state of California. It will take some balance that we don’t overdo it, but I am not afraid we are going to get to that point.”

But nobody really knows what’s in store for the state.

The Legislature relied on years of sophisticated computer modeling to understand how staying the course on the use of fossil fuels will disrupt Earth’s climate. No one, however, can point to detailed economic study of how the new goals will affect the world’s sixth-largest economy.

A preliminary analysis just released by the California Air Resources Board, which has sole authority to impose the new rules, projects a potential reduction of 25,000 to 102,000 jobs and the loss of $7 billion to $14 billion in gross state economic output. The board said those impacts are small relative to the state’s economy.

Other experts, however, note that too little is known to make solid predictions, while industry groups project severe consequences.

Although California set a goal of reducing greenhouse gases by 40% below 1990 levels, for example, the state did not collect greenhouse gas data before 1990. So no one can say how far back in its history as a state with cars and industry California will have to go to hit that emission level.

That benchmark could, however, require the state to emit no more carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases than it did as far back as the 1960s, based on national data that do not take into account California’s faster growth and more energy-efficient economy.

“It is dubious as to whether the California goal will be achieved without large economic costs,” said James Sweeney, director of Stanford University’s Precourt Energy Efficiency Center.

He added that the enhanced climate change fight will likely lead to a less diversified and more fragile state economy. “Meeting the requirement will require severe restrictions, far beyond those seen to date.”

Exactly what restrictions are not clear, because the rules have yet to be adopted.

But Sweeney’s analysis shows that the reduction in greenhouse gases will need to be eight times faster than the state has accomplished under the first climate change effort that started in 2006 — and the rate of reduction is twice as fast as what U.S. agreed to under the Paris climate agreement.

California is already digging deep into state resources for the climate battle. It spends about $2 billion on energy efficiency and renewable-energy programs, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office. And its regulatory trading systems redistribute several billion dollars a year. In total, the state allocates more on the climate battle than on state support for the University of California system.

Mary Nichols, the longtime chairwoman of the air board, acknowledges that the scale and breadth of the ramped-up regulatory effort to curtail greenhouse gases surpasses past programs.

“It is the biggest thing we have done yet in sheer volume,” she said. “It requires a level of coordination between different agencies that we haven’t seen before.”

Nichols added that every past era of environmental regulation prompted similar concerns of economic Armageddon, which proved to be unfounded.

“Individual industry sectors always overestimate the costs and underestimate the benefits and assume that you will implement it in the dumbest possible way,” she said.

It actually doesn’t much matter to the climate whether California hits its goal of cutting emissions by 40%, because the state accounts for only 1% of worldwide emissions, said Severin Borenstein, a UC Berkeley business professor and expert on renewable energy.

“More important is the technology and practices that can be exported to the rest of the world.”

Environmentalists are quick to point out that if Earth’s weather patterns continue to go haywire, it won’t just be California’s economy that comes unglued.

“Risky is what’s happening to the climate,” said environmentalist and author Bill McKibben. “Everything else is just a challenge, which once upon a time Americans were good at stepping up to.”

A Nissan Leaf is plugged into an electric-vehicle charging station

at the Malibu Country Mart. Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times

Critics, however, say that consigning Californians’ economic well-being to untested regulatory systems is reckless, and the hit on wallets has already begun.

Gasoline prices, for example, are headed up under several very complex regulatory systems, including the state’s low-carbon fuel standard and the cap-and-trade auction market.

And electricity prices will likely go up. At least half of California’s electricity must come from renewable sources by 2030, and though solar panel costs have dropped sharply and are subsidized by a 30% federal tax credit, existing long-term contracts already signed by utilities will likely continue to drive up the price of electricity, Borenstein said.

The state’s shift to natural gas for 60% of its in-state electricity generation could also lead to higher electricity prices. Gas prices have spiked 115% since March, though the impact has not yet filtered down to consumers.

When gasoline or electricity prices go up, people tend to use less. Manufacturers, however, may leave the state.

“Over the long term, manufacturers will be choosing to put their money elsewhere,” said Dorothy Rothrock, president of the California Manufacturing and Technology Assn. In 2000, California accounted for 5.6% of U.S. manufacturing investment. Today, it accounts for 1.8%, she said. A study by NERA, an economics research firm working for the manufacturers association, asserted that the climate goal could cost California households an average of $3,000 annually.

The California Energy Commission and the Public Utilities Commission have their own extensive regulatory programs to reduce energy consumption, and the climate change legislation will give them more legal backbone.

The Energy Commission, for example, has a goal that by 2020 all new homes will have to meet a net zero energy mandate, meaning solar roofs will have to supply all the home’s power while large amounts of insulation lower energy demand. Other rules apply later to government and commercial buildings.

“It means buildings will be part of the solution,” said energy commissioner David Hochschild.

But Dave Cogdill, president of the California Building Industry Assn., said the goal will add $45,000 to the average cost of a 2,500-square-foot home in California. The higher cost is likely to lead to fewer new homes, exacerbating the state’s housing and employment problems.

And a slowdown in construction could potentially reducing gross state product by $7.5 billion and employment by 75,000 jobs, said Brad Williams, an economist at Capitol Matrix Consulting who studied the legislation for the building association.

An analysis by Jeff Greenblatt, a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory expert on energy efficiency, projects that significant improvements of existing buildings will be necessary, but on a scale 30 times faster than the current rate of improvement.

“It would be a huge lift. You could incentivize it, but I don’t know how you would pay for it,” he said.

The effects of the new rules on California agribusiness could be even more significant.

“We are not saying we shouldn’t do anything for the climate,” said Roger Isom, president of the California Cotton Growers and Ginners Assn. “But it would be great if somebody was on the playing field with us. Not once did anybody ask how we could do this.”

Isom said the cotton industry is already in free fall.

Dairies are also bracing for a difficult future, said Anja Raudabaugh, executive director of the Western Dairymen’s Assn. Just this year, 53 dairies have gone bankrupt, left the state or simply closed their doors, a trend likely to accelerate, she said.

“There is no way we can manage the reductions they want,” she said.

Dairy herds produce roughly 10 million metric tons of the greenhouse gas methane each year, a consequence of cow flatulence, burping and manure.

Under SB 1383, that has to change.

At a heated meeting in June, dairy officials pleaded with the Air Resources Board that they already reduced methane emissions. Air board scientist Ryan McCarthy suggested that new technology could help, and the discussion turned to an experimental system from Argentina that would capture gas in a backpack on each cow through a hose inserted into their digestive system.

“All of our jaws hit the floor,” recalled Raudabaugh. “It is an outlandish scheme.”

Many other agriculture sectors will be facing new challenges that will drive up costs, according to Daniel A. Sumner, a UC Davis professor and director of the University of California Agricultural Issues Center. “Agriculture will be smaller along with the rest of the economy,” he said.

“We are at the point where we have to ask does agriculture fit into California’s future,” said Ryan Jacobsen, executive director of the Fresno Farm Bureau. “We can’t take anything that happened this year and say this Legislature and this governor want the agriculture industry here.”

And as the economy changes, so will people’s lives.

State law, for example, requires development of denser urban communities, where residents will drive less.

“People need to stop driving around and stop buying throw-away merchandise,” said Greenblatt, the Lawrence Berkeley scientist.

That goal may prove tough, given that Californians drove more than ever this summer, up 6% from last year.

A 20% reduction in travel miles, currently about 190 billion annually, could be needed by 2030 to meet the state’s climate goals, according to estimates by the Air Resources Board. The agency says the public can walk, bike, ride share and use transit.

“It is not draconian,” McCarthy said.

Many, in fact, say that the changes California’s climate goals will spur are long overdue and will make Californians’ lives better.

Californians, said Nichols of the Air Resources Board, could have had cleaner air, more walkable, bikeable cities, and a head start on a vibrant green economy years ago.

What impeded that, she said, is that “the entrenched power of the status quo wouldn’t let go.”

Regulations the air board is considering

The Air Resources Board is in the early stages of formulating new regulations and reinforcing existing ones to achieve massively reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The agency released a draft of its ideas in early December, representing the largest and most comprehensive regulatory effort in state history. Here are some of the possible approaches:

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions at refineries by 20%.

- Electrify boilers.

- Increase renewable electricity by more than the existing 50% statewide requirement.

- Cut greenhouse gas emissions at oil and gas fields by at least 25%.

- Work with ports to develop “super-low emission efficient ships.”

- Increase use of low-emission diesel fuels.

- Reduce the amount of driving across the state.

- Use fertilizers with lower nitrogen content.

- Cut organic waste going into landfills by 75%. Increase landfill fees.

- Improve freight transportation efficiency by 25% by 2030.

- Deploy more than 100,000 zero-emission freight vehicles by 2030.

- Have 4.3 million zero-emission vehicles operating by 2030.

- Develop zero-emission rail vehicles.

- Alter environmental rules to increase density in residential neighborhoods.

- Accelerate replacement of residential gas furnaces.

- Increase the large-scale storage of electricity.

- Develop new pipeline systems to transport renewable natural gas from farms and landfills to urban users.

- Modify the cap-and-trade auction system so that it covers the entire energy sector.

- Implement rules to require state pension funds to sell holdings in coal producing companies.

- Modify streets for more bicycle and foot travel.

Source: Los Angeles Times

December 11, 2016