[Source: East Bay Times] California’s brutal five-year drought did more than lead to water shortages and dead lawns. It increased electricity bills statewide by $2.45 billion and boosted levels of smog and greenhouse gases, according to a new study released Wednesday.

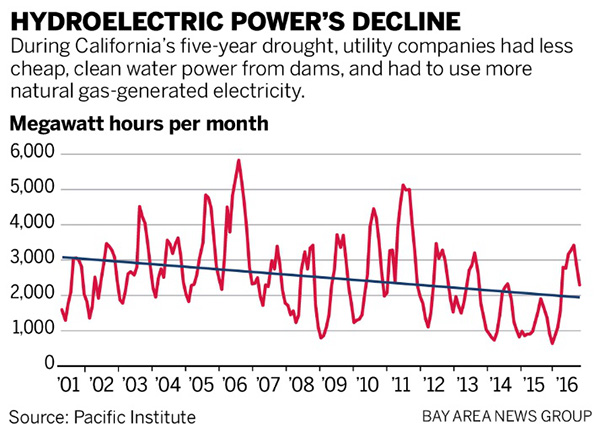

Why? A big drop-off in hydroelectric power. With little rain or snow between 2012 and 2016, cheap, clean power from dozens of large dams around California was scarce, and cities and utilities had to use more electricity from natural-gas-fired power plants, which is more expensive and pollutes more.

“The drought has cost us in ways we didn’t necessarily anticipate or think about. It cost us economically and environmentally,” said Peter Gleick, co-founder of the Pacific Institute, an Oakland-based nonprofit group that researches water issues, and author of the report.

California has 287 hydroelectric dams — from small reservoirs in the Sierra Nevada to massive hydroelectric operations at its largest reservoirs like Shasta, Oroville and Folsom. Water spins turbines and creates electricity as it is released into rivers and creeks, and although dams are expensive to build and can harm salmon and other species, once constructed, their electricity costs less than power from many other sources.

From 1983 to 2013, an average of 18 percent of California’s in-state electricity generation came from hydroelectric power. But during the drought, from 2012 to 2016, that fell nearly in half, to 10.5 percent. In the driest year, 2015, hydroelectric power made up just 7 percent of the electricity generated in California.

Although solar and wind power increased during the drought years, grid operators and other power managers still needed to boost electricity from natural gas-fired power plants. Natural gas generates less pollution than coal, which is nearly entirely phased out in California following decades of laws to reduce smog. But the extra natural gas burned during the drought increased greenhouse gas emissions from power plants in California by about 10 percent, or 24.1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide between 2012 and 2016.

That’s the same amount of heat-trapping pollution as adding 2.2 million more cars to the road over that time — or roughly doubling all the cars currently registered in Santa Clara and Contra Costa counties.

Burning that extra natural gas also similarly increased emissions of smog-forming pollutants like nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and soot, the report noted.

James Sweeney, director of the Precourt Energy Efficiency Center at Stanford University, said the findings are not surprising. He noted that in other dry years, hydroelectric power decreases and it has to be made up with other types of electricity.

The overall cost in higher power bills, $2.45 billion over five years, works out to be about $12 per person in California per year, or $60 during the entire drought, he said.

“That’s not nearly as large as the agricultural cost of the drought, or even the costs that homeowners paid for low-water appliances,” Sweeney said.

Gleick agreed that Californians took bigger financial hits during the drought in other ways. But he said it’s important for state leaders to understand that during droughts, smog worsens, greenhouse gas emissions rise and there are increased costs to the economy.

Ominously, 2014 was the hottest year ever recorded in California since modern temperature records were first taken in the late 1800s. Then that record for statewide average temperature was broken in 2015. And it was broken again in 2016. In fact, the 10 hottest years globally back to the 1880s all have occurred since 1998, according to NASA.

And as the climate continues to warm, that means more water evaporates from reservoirs. It may not mean less rainfall overall — and rainfall totals have not declined in California over the past century. But hotter weather also means less of a Sierra snowpack, and soils that dry out and require more water for farming.

Gov. Jerry Brown, who has made climate change a centerpiece of his governorship, signed a law requiring that 50 percent of the electricity generated in California by 2030 come from solar, wind and other renewable sources like biomass and geothermal. In the most recent year available, 2015, such renewable sources made up 23 percent, and are growing. Natural gas generated 60 percent, nuclear power 9 percent, hydroelectric power 7 percent and coal and other sources 1 percent.

Gleick, who has a Ph.D. in energy and resources from UC Berkeley, said that California should probably expand that renewable target beyond 50 percent.

“In the long run, if there’s a long-term reduction in hydropower in California, the question is ‘what are we replacing it with?’” he said. “At the moment we replace it with natural gas, but maybe we ought to be redoubling our efforts to build more solar and wind so that if this trend continues we are not worsening the climate problem.”

Kathryn Phillips, director of Sierra Club California, agreed. “This provides more evidence that California needs to modernize its electricity system even more rapidly,” she said.

The state should boost funding for research into storing renewable energy with large batteries so it can be used when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing, and provide more incentives for homeowners to install rooftop solar, along with other reforms, she added.

“If we don’t, we’ll be stuck with a power portfolio that pollutes more when the weather is hot and dry — as it is expected to be for sizable stretches of time in the future,” she said. “Fortunately, solar works best when it’s hot and dry and it doesn’t pollute.”

Source: East Bay Times

April 26, 2017