[Source: San Francisco Chronicle] A California program to fight climate change may now add more to the cost of gasoline than the state gas-tax increase that many voters want to repeal.

The Low Carbon Fuel Standard designed to cut greenhouse gas emissions from fuel, now adds 12 to 14 cents per gallon to the cost of gasoline sold in the state, according to an estimate from the Oil Price Information Service. The fiercely debated gas tax increase, which took effect last year to fund road repairs, added 12 cents to the state’s gasoline taxes, which were already among the country’s highest.

The fuel standard’s exact impact on prices is impossible to know. For oil companies, it is a cost of doing business in California, and each company must decide how much of that cost to pass on to consumers.

But estimates of its impact have climbed this year, due to soaring prices for a tradeable credit at the heart of the program. The credits, which traded at around $76 at this time last year, now cost $173. The program caps their price at $200, a level state analysts didn’t think California would reach for another two years.

The reason for the jump: A recent report from the California Air Resources Board suggested that the tradeable credits will become increasingly scarce in the future. So companies that need them have embarked on a buying spree.

“People are saying, ‘Hey, I should pick up these things now, because they’re only going to go up in value,’” said Denton Cinquegrana, West Coast markets editor for the Oil Price Information Service, better known as OPIS. “It’s like San Francisco real estate.”

Nor is the Low Carbon Fuel Standard the only climate program adding to California’s gasoline prices. The state’s cap-and-trade system, in which companies throughout the economy pay for each ton of greenhouse gases they emit, tacks on an additional 12 to 13 cents, according to OPIS.

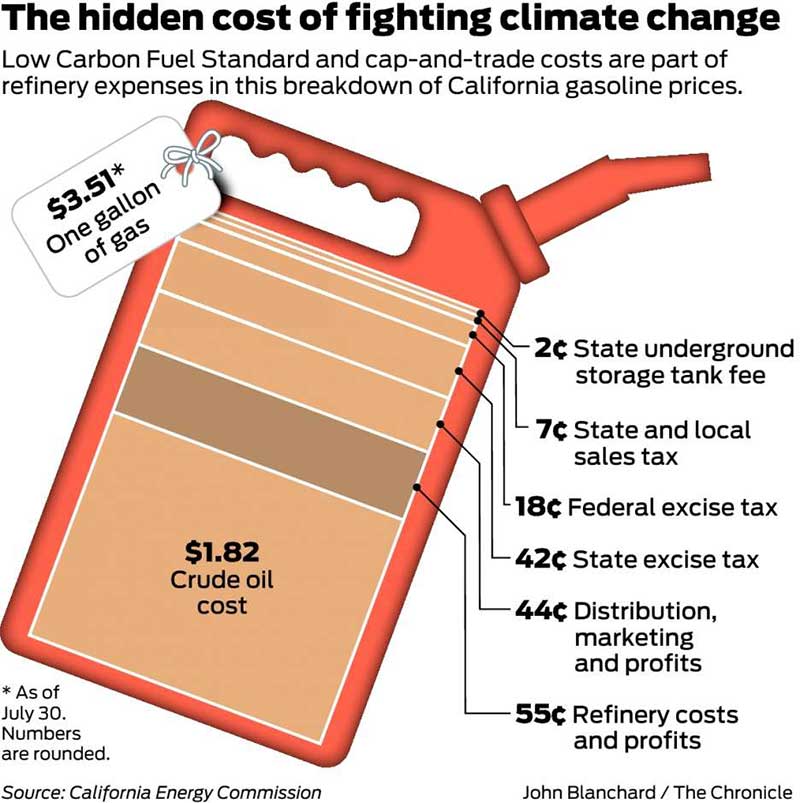

California’s gasoline prices have been slowly falling since mid-June and this week average $3.50 for a gallon of regular, according to the federal Energy Information Administration. But they remain among the highest in the United States, with only Hawaii paying more for fuel. The national average stands at $2.85.

And California has some of America’s steepest gasoline taxes.

A monthly survey from the American Petroleum Institute lobbying group found that Californians pay an average of almost 74 cents per gallon on local, state and federal taxes combined, behind only Pennsylvania, where the average is 77 cents. A weekly update from the California Energy Commission puts the total a bit lower, at 68 cents per gallon.

California’s Republican candidate for governor, John Cox, is hoping to harness voter anger over gas prices to fuel his campaign, currently viewed as a long shot in a deep blue state. In an email, Cox spokesman Matt Shupe indicated the candidate would, if elected, take a look at the programs that affect gas prices.

“First things first, we need to repeal the gas tax increase, because that’s what’s hurting California working poor today,” Shupe wrote. “Longer term, the political class has made California gas pricing complex, and as governor, he will bring together real people and experts — not the special interests that fund the current Sacramento pay-to-play system — to discuss the regulations and the most responsible way to achieve our affordability and environmental goals.”

The fuel standard has provoked opposition from the oil industry and business groups since it went into effect in 2011. But state officials consider it one of their most important weapons to fight climate change.

President Trump’s administration, meanwhile, has threatened to take away two of California’s other main weapons — the state’s ability to set its own emission standards for cars, and the “zero emission vehicles” mandate that forces automakers to sell electric cars in the state.

Although California officials have vowed to fight back in court, a victory for the White House would give even greater importance to the fuel standard. The California Air Resources Board could even consider trying to toughen the program to cut more greenhouse gas emissions than the program currently envisions.

“If somehow they were able to pull out our ability to set our own standards, and the (zero emission vehicle) mandate, then we would have to find other ways to get those reductions,” said Stanley Young, spokesman for the Air Resources Board.

The fuel standard works by setting targets for reducing a fuel’s “carbon intensity” — a measure of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with producing and using it. The carbon intensity target gets incrementally tougher year by year, lowering emissions in the process.

Oil companies can comply by blending more biofuels into their products, particularly advanced biofuels such as renewable diesel and cellulosic ethanol. Or they can buy credits from companies that sell fuels with lower carbon intensities than the target. For example, utilities whose customers use electricity to charge their electric cars generate credits the oil companies can buy.

For years, the program had little effect on California’s gasoline prices, adding perhaps 4 cents per gallon. But the impact has grown this year as prices for the credits climbed following reports issued by the Air Resources Board showing that in the fourth quarter of 2017 and the first quarter of this year, the number of new credits generated within the system was less than the amount that companies needed to comply. In other words, for those two quarters, demand for the credits outstripped new supply.

The program was designed to ensure that in its early years, the number of credits generated each quarter would greatly exceed demand. That allowed the oil companies to build up a bank of credits to use once the intensity targets grew harder to meet. So companies are now dipping into their banked credits. And the belief that the amount of new credits generated will continue to lag demand is driving the price toward its ceiling.

“The market’s anticipating that to be an ongoing trend, where deficits exceed credits,” Cinquegrana said.

For months, the Air Resources Board has been considering changes that would take some of the immediate pressure off oil companies. Instead of needing to cut the carbon intensity of their fuels 10 percent by 2020, the companies would need to reach that level in 2022.

However, the changes would also extend the program through 2030, setting tougher targets for the companies to meet in 12 years. By 2030, fuel providers would need to cut carbon intensity by 20 percent, compared with 2010 levels.

A decision could come as soon as next month.

“No one’s looking to require more than what’s possible, but at the same time, the regulators want to make sure the oil companies are doing as much as they can to reduce their carbon footprint,” said Simon Mui, a senior scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. He called the fuel standard one of the state’s most effective climate policies, cutting an estimated 35 million metric tons of emissions so far.

“Certainly with the federal government attacking clean vehicle policies, California’s other programs will become even more critical,” he said.

Source: San Francisco Chronicle

August 9, 2018