[Source: The Mercury News] California is already a world leader in developing environmental policies that address climate change.

But under a landmark bill sent to Gov. Jerry Brown on Wednesday requiring far steeper reductions in greenhouse gas emissions than anything the state has ever attempted, the next 15 years will likely see big changes for California residents.

Among the possibilities, experts say:

Rules requiring automakers to make hundreds of thousands of electric cars. Penalties for people who buy gasoline-powered vehicles. New tax credits and incentives for solar farms and wind power. Tighter building-efficiency standards on windows, heating and water systems in homes and businesses.

Labels at the supermarket showing each product’s carbon footprint. Hydrogen-powered trucks. Landfills that are required to capture natural gas and use it to heat homes. A big push for batteries to store energy at homes.

Even with all those changes, however, the new targets will be difficult to reach.

“This is going to be damn hard,” said Jim Sweeney, director of the Precourt Energy Efficiency Center at Stanford University. “It’s a herculean task.”

The task is spelled out in Senate Bill 32, which lawmakers passed after more than a year of debate. Under the measure, California is required to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, despite population and economic growth.

The measure, a key victory for Brown, builds on AB 32, a law signed in 2006 by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger that required the state to cut emissions to 1990 levels by 2020.

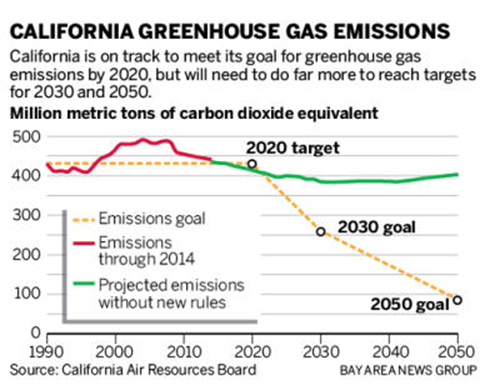

California is on track to meet that goal, having already cut emissions 9.4 percent from their peak in 2004, but to cut them another 40 percent in a decade and a half will require a host of new rules and incentives from the California Air Resources Board and other state agencies in the coming years, along with some new laws from the Legislature.

Studies by scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab lay the math out clearly. In 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, California emitted 441 million metric tons of greenhouse gases. The target for 2020 is 431, but emissions will have to fall to roughly 260 to meet the target in state Sen. Fran Pavley’s bill.

There are key existing laws already in place that will help. For example, Brown signed a law last year requiring that the state’s utilities produce 50 percent of their electricity from solar, wind and other renewable sources by 2030. And in 2009, President Barack Obama required automakers to double gas mileage standards nationwide from an average of 27 miles per gallon to 54 by 2025.

Both edicts — and others like them — mean far less coal, gasoline and natural gas will be burned, cleaning up the environment and reducing emissions that warm the planet.

Yet even with the huge savings from those laws, California will still get to only about 375 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 — or about a third of the way to the 2030 goal, according to Lawrence Berkeley lab estimates.

“We are going to need some additional policies to get us all the way there,” said Jeffery Greenblatt, a staff scientist in the lab’s energy analysis division.

Greenblatt said it is certainly possible for the state to meet the goals if it strengthens existing clean energy rules and draws up more.

“There are many ways to get there,” he said.

California could increase the renewable energy requirement beyond 50 percent, he said. Or it could begin to reduce the carbon footprint of natural gas that is used commonly in homes and businesses by requiring “recycled” natural gas from landfills to be mixed in with it. Or it could pass building rules requiring most appliances that now run on natural gas to run on electricity. It could require companies to use hybrid vehicles for delivery trucks, electrify diesel trains and expand research and incentives for home battery storage, so people could power their homes with electricity from their vehicle batteries while their electric cars sit in the driveway.

SB 32 was supported by a wide variety of organizations, from the Sierra Club to the American Cancer Society. It also had the backing of businesses that make alternative energy and vehicles, including the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, General Motors, Ford and PG&E.

However, it was strongly opposed by traditional industries such as oil, cement and manufacturing.

Passage of the bill “is not a reason to celebrate,” said Catherine Reheis-Boyd, president of the Western States Petroleum Association.

She worries that the Air Resources Board, an agency created by Gov. Ronald Reagan in the 1960s to reduce smog, has too much power to write the rules. Despite last week’s passage of a companion bill to address that concern, she said, “There is no accountability in providing blank check authority to a state bureaucracy.”

Similarly, Dorothy Rothrock, president of the California Manufacturers & Technology Association, said if more regulations are placed on manufacturing, companies will leave the state.

“California is still subjecting its manufacturers to costs that other states aren’t imposing,” she said.

Mary Nichols, chairwoman of the air board, said that industry for decades has overstated the risks of environmental rules in California, and the targets are nearly always reached by innovation.

“There’s no question it is a challenge,” Nichols said, “but we’ll build on the momentum that we are already doing. It will mean more renewable energy, more low-carbon fuels and more vehicles that run on electricity and fuel cells.”

An executive order signed by Schwarzenegger 11 years ago also sets a general goal of 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gases by 2050, although it has not been approved by the Legislature.

The science on climate change is clear.

The 10 hottest years worldwide since 1880, when modern measurements began, all have occurred since 1998, according to NASA. Last year was the hottest year in recorded history, and 2016 is on pace to break the record again, increasing the risk of forest fires, droughts and flooding from rising sea levels.

California’s climate rules on cars, buildings and other areas already have been copied by other states and nations, supporters note.

The state has cut greenhouse gas emissions nearly 10 percent since 2004. And during that time, the state’s annual economic output has grown from $1.5 trillion to $2.2 trillion.

“Over the past 10 years, our economy has increased and emissions have gone down,” said Pavley, D-Agoura Hills, who wrote SB 32. “We have created new jobs in solar and other industries.”

Dan Kammen, director of the renewable energy lab at UC Berkeley, said the new rules will spur innovation and investment, as previous California environmental laws have done.

“Utilities will be like eBay, brokering electricity sales from people’s rooftop solar systems,” he said. “We’re going to see homes built that have no natural gas lines to them, and solar on the roof with battery storage. You are going to see buildings built with chemical batteries built into the foundation to store energy.”

California’s 40 percent reduction target by 2030 is similar to goals set by the European Union — regulations that scientists say are necessary to limit warming to about 4 degrees Fahrenheit over the rest of this century.

“The effort to decarbonize our economy in California and throughout the world is extremely difficult,” Brown said last week. “It’s a tall hill, and we’re climbing.”

Source: The Mercury News

August 29, 2016