[Source: Los Angeles Times] For some California commuters, cutting down on carbon emissions isn’t a sexy enough reason to buy an electric car. But the ability to bypass freeway traffic without having to carpool — that’s another story.

So there is grumbling in high-occupancy-vehicle lanes across California these days. On Jan. 1, the owners of as many as 220,000 low- and zero-emission vehicles stand to lose the white and green clean-air decals that allow them to drive solo in the diamond lanes.

The decal program was designed to get more clean-air vehicles on state roadways. But it also clogged the lanes, sometimes to the point of gridlock.

So the state Legislature passed a measure last year that significantly limits the number of people eligible for these decals. As of New Year’s Day, drivers who received their clean-air stickers before 2017 will have to buy new vehicles to qualify for the program, or purchase used cars that have never had a decal but would have qualified for one in 2017 or 2018.

And some who earn above a certain amount won’t be eligible for the stickers at all.

Clean-air advocates say that the new policy unfairly punishes early adopters of electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, and will discourage drivers who can’t afford to buy a newer zero-emission vehicle — but may have purchased a used one to secure the carpool benefit — from entering the electric vehicle market.

“There need to be continued incentives to get people to drive electric,” said Katherine Stainken, policy director for Plug in America, a Los Angeles electric vehicle advocacy group. “And we’re not making it easy for someone to make that choice.”

One reason for the backlash is that carpool lanes are also being shared by large numbers of cheaters who illegally drive their fuel-burning cars solo in the lanes to cut down on their commutes.

In some parts of the state, 1 in 4 vehicles in diamond lanes are there illegally, according to Caltrans.

Those who face losing their stickers argue authorities should crack down on the cheaters before turning to those who bought fuel-efficient cars.

Dave Moreno of Glendale, who will lose the clean-air decal for his 2013 Prius, said he finds it ridiculous that electric car drivers are the ones being penalized for this problem. The 68-year-old said he regularly sees single-occupancy gas guzzlers weaving in and out of carpool lanes. He thinks the California Highway Patrol should monitor the lanes in vehicles emblazoned with the words “HOV Patrol.”

“There needs to be a message that the CHP is taking enforcement seriously,” Moreno said. “I’m honestly not seeing it.”

The CHP is doing everything it can to enforce HOV-lane law, CHP Officer Kevin Tao said. But the agency’s resources are spread thin. About 230 officers are responsible for patrolling 915 miles of freeways and highways in Los Angeles County at any given time, Tao said. And responding to collisions, disabled vehicles and other traffic hazards takes priority over issuing the $491 citations to cheating carpool lane users.

“Because people don’t see us sitting next to the carpool lanes, they assume we aren’t doing our jobs out there,” he said.

To meet federal requirements, a diamond lane must move at an average of 45 mph during peak commute hours. In 2016, California’s highways met that benchmark only 32% of the time, Caltrans data show, explaining the sudden push to reduce carpool-lane traffic.

There are solutions to this problem that would spare clean-air drivers, such as increasing vehicle occupancy requirements to three or more people; instituting or increasing tolls; or constructing more diamond lanes, according to Caltrans. But those fixes are either cost-prohibitive or politically unpopular, said Stuart Cohen, executive director of TransForm, an Oakland transportation advocacy group.

“This is absolutely the simplest way to tackle this issue,” Cohen said.

It may be the simplest solution, but it is not necessarily the most logical. An estimated 8% of vehicles using carpool lanes in Los Angeles County have clean-air stickers, according to Caltrans. The agency said it has been unable to determine a correlation between decaled vehicles and lethargic diamond lanes.

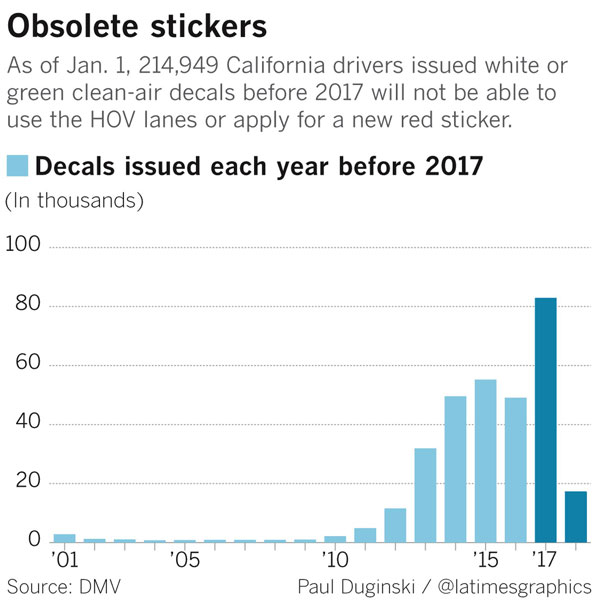

The exact number of drivers who will be affected by the decal policy changes is unclear. The 132,733 vehicles issued a white or green decal in 2017 or 2018 are eligible to apply for a sticker, which will provide access to diamond lanes until Jan. 1, 2022. The 214,949 drivers who got their decals before 2017 will be issued a sticker only if they buy a new car. Vehicles that would have been eligible for decals in 2017 and 2018 — but never received one — may also qualify for a sticker.

Further complicating matters are the new income thresholds placed on sticker-holders with fuel-cell vehicles. Single filers who make more than $150,000 a year and households that earn more than $300,000 must choose between a clean vehicle rebate and the decal. This does not apply to plug-in or battery-run cars.

Jeff U’Ren, a 2017 Chevy Bolt driver who has already received the rebate, said that the income cutoff — which he exceeds — seems “ambiguous.”

“It doesn’t really help our state in its cause to replace fossil-fuel burners with non-polluting vehicles,” U’Ren said.

This policy change comes at a crucial time for the state as it strives to meet climate change goals. This year, Gov. Jerry Brown issued an executive order calling for 5 million zero-emission vehicles to be on the road by 2030. But only about 400,000 zero-emission cars have been sold so far in California.

One way to get more people into electric cars is to promote those sold in the pre-owned market. But clean-air decals will no longer be available to most older models — and that could make all the difference for low-wage earners who are on the fence when it comes to buying a zero-emission vehicle, advocates say. A recent UCLA study found the ability to drive alone in a carpool lane or a toll lane is the “single biggest incentive” for Californians to buy a zero-emission vehicle if they live within 10 miles of such a lane.

On Thursday, Brown signed a bill that would allow residents who make below 80% of the state’s median household income — about $54,000 a year — to buy decals for some used cars that were already issued white and green stickers. That regulation goes into effect in 2020.

But there are drivers who fall into the financial in-between, including Kitty Adams of Torrance. Adams, a single mother of three who is temporarily leasing a 2002 electric Toyota RAV4 from a friend, said the carpool lane shaves 30 to 45 minutes off her commute. The decal allows her to pick up and drop off her kids at school on time.

Adams is in the market for a used electric car that costs about $10,000. She cannot comfortably afford a new one.

“Not being able to use the carpool lane will definitely affect my day-to-day,” she said.

In Greater L.A., some environmentally minded commuters will be doubly hit. In April, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority opted to end a program granting solo drivers of zero-emission vehicles free access to the carpool lanes on the 110 and 10 freeways. Drivers with clean-air stickers will be charged a toll starting in November or December of this year, though they will receive a 15% discount on the per-mile toll lane price.

For Marvin Campbell of Culver City, this tangle of local and state regulations is enough to make him consider buying a new car.

The 57-year-old treadmill mechanic said he’s not convinced that electric vehicles are clogging carpool lanes. But he commutes about 14,000 miles each year and can’t imagine traveling without the decal. So he’ll probably replace his trusty electric Kia Soul — even though it’s just 2 years old.

Source: Los Angeles Times

September 17, 2018